Можно.. нельзя.. льзя??

You may have learned the words можно (‘permitted, allowed, may’) and, as its opposite, нельзя – ‘not allowed, not permitted, forbidden.’ Have you ever wondered why the opposite of нельзя isn’t just… льзя?

Marina Koroleva (that’s Королёва!) had a nice column in Российская газета about this a while back. She begins with a little joke:

– Что ты делаешь? Нельзя!

– Может, кому-то и нельзя, а мне… льзя.

(Loosely translated: -What are you doing? That’s not allowed! -Maybe some people aren’t allowed.. but I am.)

Most Russians would chuckle at this: after all, practically nobody says льзя. But as it turns out, льзя is – or rather, was – a word in Russian.

Koroleva points out that while it’s uncommon now, you can find льзя in Dal’s dictionary, and examples can be found in Dostoevsky and Gogol. If you dig back far enough, you’ll find it’s related to words like лёгкий and льгота.

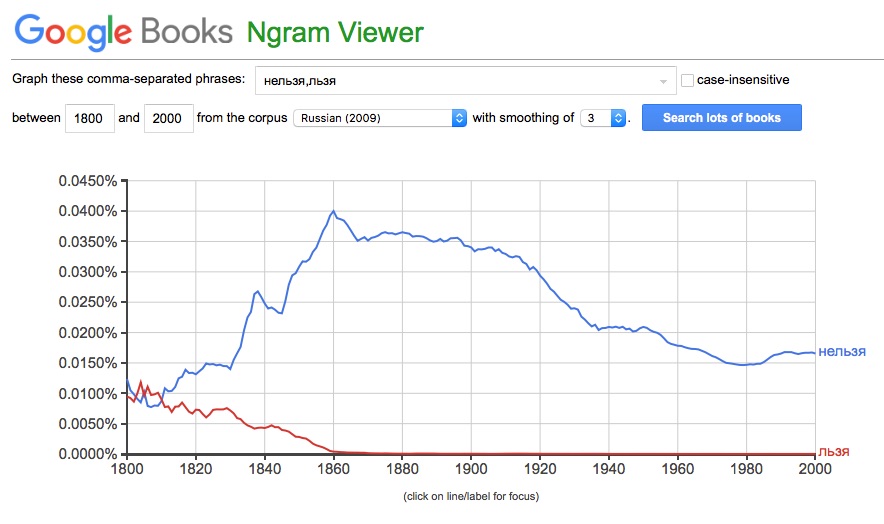

Perhaps an image from Google’s Ngram Viewer is the best way to understand the fates of льзя and нельзя. Back around 1800, льзя seems to have been just as common as нельзя. For whatever reason, its fortunes began to decline to the point where Google finds almost no examples by around 1870.

I’ll leave the last word to Kornei Chukovski. From his book on the creative ways children experiment with language, От двух до пяти:

Другое старинное слово я слышал от детей много раз, когда говорил им «нельзя». Они отвечали: «Нет, льзя». И это льзя напоминало Державина: Льзя ли розой не назвать? Льзя, лепый, вежа, чаянно ― эти старинные слова умерли лет полтораста назад, и ребенок, не подозревая об этом, воскрешает их лишь потому, что ему неизвестна их неразрывная спайка с частицей «не», установившаяся в давней традиции.

Many times I’ve heard another old word from children when I’ve told them, “That’s not allowed.” They answered, “Yes, it is [льзя].” And this льзя reminds one of Derzhavin: Льзя ли розой не назвать? Can one not call it a rose? Льзя, лепый, вежа, чаянно – these old words died about 150 years ago, and a child unsuspectingly resurrects them, simply because he does not know about the indivisible connection with the particle не (not), long established in tradition.

Unpaired Opposites in English

Russian is not the only language with this kind of unpaired opposite. Jack Winter’s “How I Met My Wife,” a popular piece among linguists and word-nerds, begins like this:

“It had been a rough day, so when I walked into the party I was very chalant, despite my efforts to appear gruntled and consolate.

I was furling my wieldy umbrella for the coat check…”

The joke is that in English, some words seem to exist only with a prefix: we can say nonchalant, disgruntled, disconsolate, and unwieldy; but “chalant,” “gruntled,” “consolate,” “furl,” and “wieldy” don’t exist.

If you’re curious, here’s a little more about this history of a few of these English examples..